To Raise or Not to Raise: The History & Impact of the Federal Debt Ceiling

This year's headlines have given rise to several short-term concerns for investors, including the ongoing debate about the federal debt ceiling.

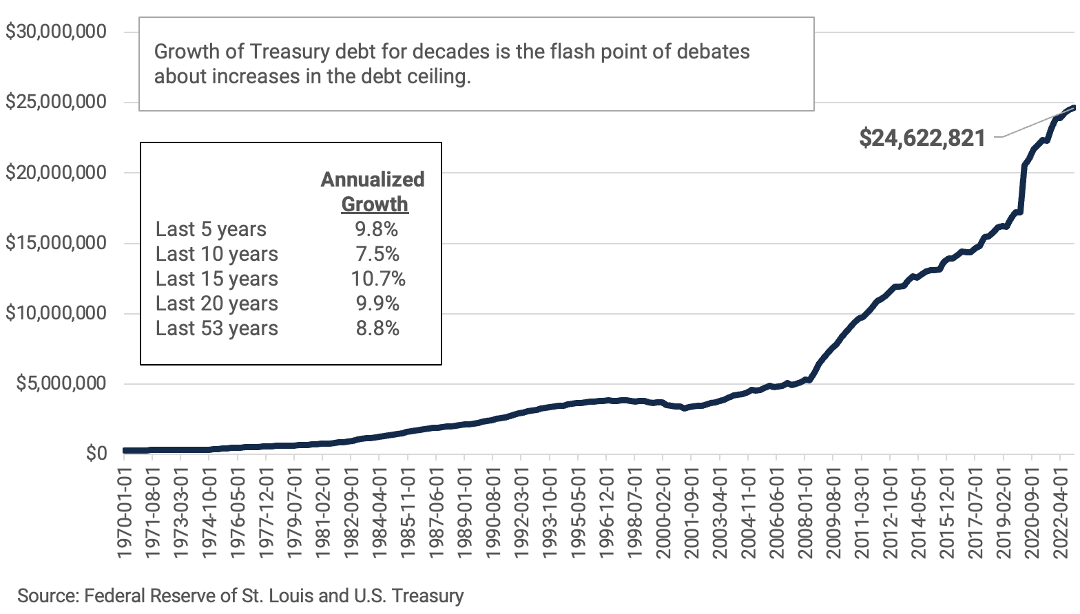

Over the past decade, some members of Congress have argued that the debt limit should not be increased unless there are reductions in federal spending to decrease the overall federal debt level. The Speaker of the House has supported this approach by stating that certain House members will only vote in favor of raising the debt limit if there is an agreement to cut federal spending. The validity of this perspective is supported by the size of the federal debt and the rapid increase in outstanding Treasury debt held by the public since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 to 2009. For investors to maintain some perspective on this issue, it is important to understand some of the terms used during this debate and to learn from past negotiations over the debt limit.

Exhibit 1: Treasury Debt Held By the Public ($ in millions)

What Is the Federal Debt Ceiling?

In 1917, Congress set a limit known as the debt ceiling, or, the amount of outstanding debt the federal government can carry. Currently, the government's total outstanding debt is $31.4 trillion.[i] That is the limit Congress last approved in December of 2021. The ceiling can be raised again only with an approval vote from both houses of Congress.

The limit needs to be continually raised because the government regularly spends more than it takes in through taxes and other revenue. When that happens, it creates a deficit, the annual shortfall in revenue vs. expenses. The annual budget deficit is distinct from the total amount of outstanding debt. For the fiscal year 2022, the federal deficit was $1.38 trillion.[ii] The last time the federal government ran a surplus by bringing in annual revenue that exceeded expenditures was in 2001. In the following two decades, the federal government regularly ran deficits. The annual revenue shortfalls spiked during the economic slowdown during the pandemic, with the annual deficit reaching $3.13 trillion in 2020 and $2.77 trillion in 2021.[iii]

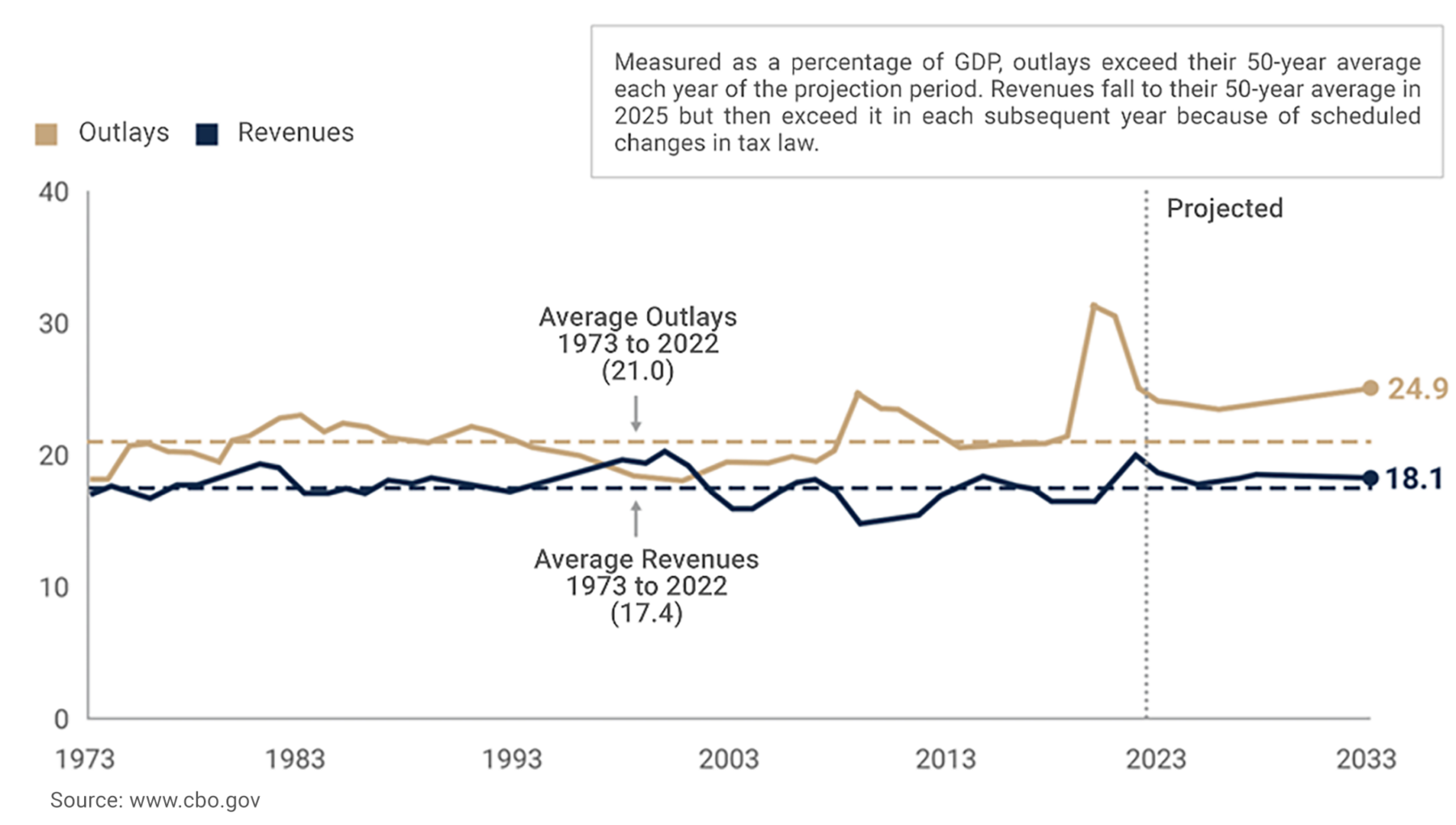

As Exhibit 2 illustrates, federal expenditures are expected to account for a larger share of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) over the next 10 years. Given that government revenues, also viewed as a percentage of GDP, are expected to remain relatively flat through 2033, the federal deficit and the country's overall debt level will likely keep increasing, thereby creating the need for additional debt ceiling votes.

Exhibit 2: The Federal Government’s Total Outlays vs. Revenues, as a Percentage of GDP

It should also be noted that a vote to raise the debt ceiling does not authorize the government to spend more, thereby increasing the debt further. Instead, it is simply a vote to allow the Treasury to borrow more to cover the costs associated with federal spending obligations already approved in past legislation.

What Are This Year’s Deadlines?

The government hit the previously approved debt ceiling on January 19, 2023. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was able to delay the time Congress needs to vote on lifting the debt ceiling by taking steps that have been used during previous debt-ceiling debates, known as "extraordinary measures."

These steps, which the Treasury has been authorized to take by Congress, include suspending certain intragovernmental debt and borrowing to fund programs and services for a limited time after the debt ceiling has been reached. These measures can only delay, and not remove, the need for a Congressional vote.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that these measures to help the Treasury Department meet its obligations will be exhausted by the third quarter of this calendar year (the fourth quarter of the government's fiscal year).[iv]

If Congress does not raise the debt ceiling before then, the government might have to delay some of its payment activities, including Social Security benefits and federal government employee payrolls, sometime between July and September, according to the CBO.

The Treasury Department also might begin to miss interest and principal payments owed to its bondholders. To avoid all the potential negative consequences of this outcome, Congress would need to vote to raise the debt ceiling, ideally before July 1.

What Happens if the Ceiling Is Not Increased?

If the debt ceiling is not lifted and payments to investors in Treasury securities cannot be made, the U.S. government, deemed the most creditworthy of all issuers of sovereign debt, would be in default. That would have significant implications for the global and U.S. economies, given that U.S. Treasuries and the U.S. dollar are considered safe havens for investors worldwide.

If the government could not raise more debt to fund its obligations, investors in U.S. Treasuries would not be the only ones affected. The government, faced with a financing shortfall, would have to impose additional cuts in its expenditures, such as lowering benefits paid to Social Security recipients or payments made to federal employees.

The shock of this scenario unfolding would likely cause significant volatility in the stock and bond markets. Interest rates would likely increase, raising consumers' borrowing costs for credit card balances, auto loans and mortgages. The ensuing disruption and carry-on effects could put the U.S. economy into a recession, which could threaten corporate earnings and bring significant job losses.

Are Other Steps Possible to Raise the Debt Limit?

A Congressional vote is not the only way to address the debt ceiling issue. Some have suggested the Treasury could mint a platinum coin worth $1 trillion and use its value to meet the government's debt obligations.

The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution also states that the "validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned." Some legal scholars suggest President Biden could invoke the 14th Amendment to authorize the Treasury to continue borrowing without Congressional approval.

Still, most analysts agree that these alternative options would be difficult to implement — likely worsening the impact of a possible government credit default in the future — and are thus unlikely to occur.

What Lessons Does History Teach?

For more than 90 years after a Congressional vote on the debt ceiling became a requirement, the decision was a relatively routine exercise in Washington. Until the past decade, it had not been a partisan issue.

As the U.S. Treasury notes, from 1960 to 2011, Congress had acted 78 times to permanently raise, temporarily extend or revise the definition of the debt limit. During that period, Congress did so 49 times when a Republican was president and 29 times when a Democrat occupied the White House.[v]

Raising the debt ceiling became a proper subject of debate in 2011 when congressional disagreements over spending and the overall debt load disrupted proceedings. These debates, and the financial market's reactions to them, offer some insights into how investors might view this year's negotiations over the debt-ceiling vote.

In 2011: After the mid-year election during President Barack Obama's first term in office, Republicans took control of the House of Representatives. Under the leadership of John Boehner, the Speaker of the House at that time, disagreements over certain spending reductions to reduce the overall debt level made finding a resolution difficult.

That debate led to the passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011, which introduced various measures to help reduce the budget deficit and the national debt. Still, the vote to raise the debt ceiling did not come until the eleventh hour — just days before an August 2 deadline.

The drama over whether Congress would finally vote to raise the debt ceiling caused considerable turmoil in the financial markets. Stocks had a volatile year, although the debt-ceiling debate was not the only worry roiling markets. Europe's sovereign debt crisis also negatively impacted global markets. In response to the crisis caused by the delayed vote on the debt ceiling, one of the three major credit rating agencies, Standard & Poor's, downgraded its rating of U.S. government debt from its highest rating ("AAA") to its second-highest rating ("AA+"). The other two credit rating agencies, Fitch and Moody, took no action.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated that the delay in the vote, and the uncertainty it created for Treasury markets, increased the government's borrowing costs by $1.3 billion in the fiscal year 2011 alone.[vi]

In 2013: The debt-limit debate again reached crisis levels. Again, spending reductions, including defunding the Affordable Care Act, the Obama Administration-sponsored legislation that raised government spending to increase health insurance access, were the catalysts for the debate.

In February, Congress passed the No Budget, No Pay Act, which suspended the debt limit until May. It was the first time in the debt limit's history that the issue was addressed with a suspension rather than a specific dollar-amount increase in the debt limit.

In May, when the deadline was reached again, the U.S. Treasury needed to resort to its "extraordinary measures" to avoid defaulting on its obligations.

The debate over the debt limit and federal spending caused the government to begin a partial shutdown, as 800,000 federal workers were put on temporary leave — lasting for 16 days. Over the following months, more legislation was passed to provide funding for the government. It was in February 2014 that the debt ceiling was increased, without any conditions, until 2015.

The U.S. stock market took all this Washington maneuvering in stride during the year and did not experience any significant volatility in response to it. This time, Fitch Ratings, early in the year, warned that a failure to raise the debt ceiling or address the issues caused by the federal budget deficit could cause it to downgrade its rating for U.S. government debt. However, the rating agency did not end up doing so.

In 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2021: Congress voted to raise the debt limit or suspend the decision by pushing it out to a later date. The debates over these votes did not reach the crisis levels seen in 2011 and 2013.

A Different Impact on Stocks and Bonds

The equity market's reactions to the debt-ceiling crises of 2011 and 2013 demonstrate that decidedly different scenarios can play out. With the perspective of a longer timeframe, it also becomes clear that the bond and stock markets can respond differently to debt ceiling negotiations and the eventual decision to increase the federal debt limit.

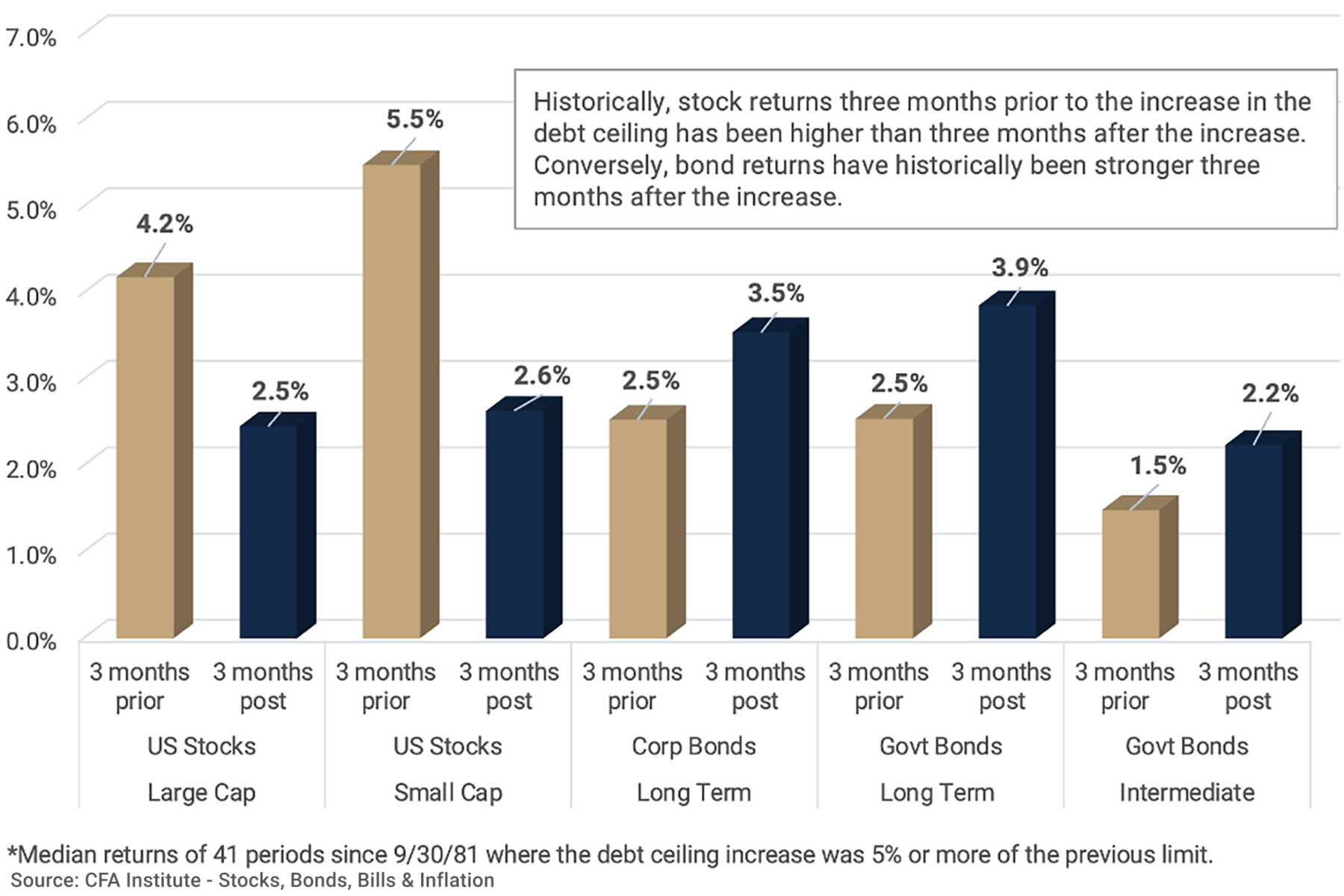

Exhibit 3 shows that over the 41 periods since September 30, 1981, when the debt ceiling was increased by more than 5%, the total returns for stocks fared worse in the three months after the decision than in the three months prior. Alternatively, bonds across significant categories, including intermediate- and long-term government bonds and long-term corporate bonds, posted better returns in the three months after.

Exhibit 3: Capital Market Returns Prior and Post Debt Ceiling Increases

Intuitively, these varied responses make sense. Equity markets responded to the fact that more government spending would have to be committed to servicing a higher debt level. That could curb the economic growth that can fuel the expansions that propel corporate earnings growth.

Alternatively, an end to concerns about the U.S. government defaulting on its debt brings relief for investors in all types of bonds that would be negatively impacted by that development.

Perhaps the fundamental conclusion that can be drawn from this analysis, however, is that financial markets still, on average, delivered positive returns in the months leading up to and the quarter after a vote on the debt ceiling, implying that such votes ultimately have little lasting impact on markets in either direction.

While the headlines during these debt-ceiling debates might cause alarm, the historical returns suggest there is no need for panic.

What Can Investors Expect from This Year’s Debt-Ceiling Debate?

Given that multiple factors can influence the performance of financial markets in any given year, it can be difficult to predict what impact the current debate on the debt ceiling will have on stock and bond market returns for 2023. Again, the impact, if any, could also vary between the two asset classes.

For stocks: Generally, the stock market does not like uncertainty, and doubt about whether Congress will vote to raise the debt ceiling creates uncertainty. In 2023, U.S. stocks are coming off a challenging year, as the S&P 500 Index was down by 20% in 2022. That decline was caused by several factors, including the global supply chain challenges created by the pandemic and the imbalance between supply and demand, as consumer spending surged in the aftermath of lockdowns.

That imbalance and geopolitical tensions, such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine, caused inflation to skyrocket. The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) acted to curb inflation by raising interest rates.

The question going into 2023 was whether the Fed would be able to rein in inflation enough without having its continual rate increases lead the economy into a prolonged recession. The closing of Silicon Valley Bank by regulators added to investors' worries, as some feared the collapse of that bank might cause a broader crisis across the banking sector.

The debt-ceiling debate is just one part of a larger picture investors must consider. While weighing current conditions, it is also critical to keep in mind that while single events can garner a lot of negative headlines and cause short-term market disruptions, the fundamentals of the economy and individual companies' fundamentals have a greater impact on long-term investment returns.

Despite high inflation, several economic fundamentals have remained strong, including employment levels and consumer spending. Similarly, it is important to consider fundamentals like debt levels and earnings growth at the company level.

In recent years, many companies have had healthy balance sheets with low levels of debt. While earnings growth can vacillate from quarter to quarter, investors should keep an eye on the long-term trend for earnings.

These factors have historically influenced the total returns provided by equities more than the short-term concerns raised by the uncertainty over an upcoming vote on the debt ceiling.

For bonds: 2022 was also a challenging year for fixed income investors; the four-decades-long bull market for bonds ended when the Fed began steadily raising its benchmark federal funds rate from a level that had effectively been zero.

Rate increases bring declines in bond prices, creating a challenging market for bond investors. Absent the implications of the debt-ceiling vote, the bond market has been trying to gauge if and when the Fed will begin to moderate its rate hikes.

If Congress does not raise the debt ceiling before July, any resulting default would have immediate consequences. A default would shake the faith in the U.S. government as the most creditworthy of all bond issuers.

In contrast, a vote to raise the debt limit could prevent those dominoes from quickly falling and provide a short-term boost for bond returns, as it has in the past. Still, a vote to raise the debt ceiling without any effort to lower the federal budget deficits and reduce the overall federal debt could also have negative long-term consequences.

The burdens of the government carrying a heavier debt load could hinder the country's economic growth. The rating agencies could also view that higher debt level as a cause to downgrade U.S. debt, which would increase borrowing costs for the U.S. government and have a negative ripple effect across all fixed income markets.

What Can Investors Do?

In periods of market volatility, investors' instinct is to try to escape the turbulence by retreating to the sidelines or limiting their exposure to certain market segments.

However, exiting the financial markets and increasing cash positions can adversely impact long-term returns. When markets rally, they often do so in quick and sudden bursts. Timing the markets by trying to guess the best times to exit and reenter is nearly impossible to do successfully with any consistency.

Investors typically leave at the bottom of the market and get back in after a rally has already begun, meaning they have missed a good portion of the rebound. A retreat to the sidelines often causes investors to capture the losses they incurred at the trough of the downturn, whereas staying invested through short-term turbulence would have seen them capture all of the potential upsides.

At Wilbanks Smith & Thomas Asset Management, we have not seen any issues related to the debt-ceiling debate that have caused us to make any significant adjustments in the portfolios we manage. Further, no other key economic fundamentals, beyond the ongoing issues of inflation and interest rates and their impact on economic growth, give us significant cause for concern. As always, we will continue monitoring developments throughout the year and respond if any scenario that warrants major adjustments to investment allocations arises.

When external events like the debate over the debt ceiling cause turbulence in the markets, we return to the principles that have always guided our approach. Thoughtful diversification, long-term thinking, and making decisions based on facts and fundamentals, not emotions, remain the pillars of our approach to managing clients' portfolios according to their needs and objectives. We understand that events like this can spark worry and questions, which is why we always encourage honest, clear communication. As the debt ceiling debate continues to develop, we welcome the opportunity to connect and look forward to a visit or conversation soon.

References:

[i] Source: “What Is the national debt?” fiscaldata.treasury.gov, as of 3/13/23

[ii] Source: “What is the national deficit?” fiscaldata.treasury.gov, as of 3/13/23

[iii] Source: “What is the national deficit?” fiscaldata.treasury.gov, as of 3/13/23

[iv] Source: “Federal Debt and the Statutory Limit,” Congressional Budget Office, February 2023

[v] Source: “Debt Limit: Myth vs. Fact,” Department of the Treasury, May 2011

[vi] Source: “Debt Limit: Analysis of 2011-2012 Actions Taken and Effect of Delayed Increase on Borrowing Costs,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, 7/23/12

Important Disclosures

Wilbanks, Smith & Thomas Asset Management (WST) is an investment adviser registered under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training. The information presented in the material is general in nature and is not designed to address your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. Prior to making any investment decision, you should assess, or seek advice from a professional regarding whether any particular transaction is relevant or appropriate to your individual circumstances. This material is not intended to replace the advice of a qualified tax advisor, attorney, or accountant. Consultation with the appropriate professional should be done before any financial commitments regarding the issues related to the situation are made.

This document is intended for informational purposes only and should not be otherwise disseminated to other third parties. Past performance or results should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of future performance or results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied is made regarding future performance or results. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to purchase, any security, future or other financial instrument or product. This material is proprietary and being provided on a confidential basis, and may not be reproduced, transferred or distributed in any form without prior written permission from WST. WST reserves the right at any time and without notice to change, amend, or cease publication of the information. The information contained herein includes information that has been obtained from third party sources and has not been independently verified. It is made available on an "as is" basis without warranty and does not represent the performance of any specific investment strategy.

Some of the information enclosed may represent opinions of WST and are subject to change from time to time and do not constitute a recommendation to purchase and sale any security nor to engage in any particular investment strategy. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but cannot be guaranteed for accuracy.

Besides attributed information, this material is proprietary and may not be reproduced, transferred or distributed in any form without prior written permission from WST. WST reserves the right at any time and without notice to change, amend, or cease publication of the information. This material has been prepared solely for informative purposes. The information contained herein may include information that has been obtained from third party sources and has not been independently verified. It is made available on an “as is” basis without warranty. This document is intended for clients for informational purposes only and should not be otherwise disseminated to other third parties. Past performance or results should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of future performance or results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied is made regarding future performance or results. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to purchase, any security, future or other financial instrument or product.